Schools and further education colleges in England are required to provide impartial careers guidance to their students.

The quality of this advice has come in for frequent criticism despite government reforms aimed at improving quality such as the establishment of the National Careers Service and Careers and Enterprise Company.

This month, the Commons' sub-committee on education, skills and the economy hit out at an "unacceptable" lack of action on the part of government, including the failure to produce a long-promised careers strategy.

Earlier this year the committee published a report that made several key recommendations including the introduction of a specific Ofsted judgment for careers guidance with schools unable to be rated "outstanding" overall if their careers provision was judged "requires improvement" or worse and unable to be rated "good" if careers guidance was "inadequate".

However, the government decided against taking this step.

There has been much scrutiny of careers provision since it became the responsibility of schools in 2012 with the duty extended in 2013 to encompass years 8 to 13.

Statutory guidance published by the Department for Education, updated in March 2015, sets out schools' obligations including the need to work with local employers and other education and training providers to ensure "young people can benefit from direct, motivating and exciting experience of the world of work to inform decisions about future education and training options".

The guidance also sets out expectations around quality such as the fact schools should seek to achieve one of the accredited quality awards for careers provision and check the quality of independent careers services coming in to advise pupils.

There is much debate over how well schools are fulfilling their duties. Most inquiries and investigations paint a picture of patchy provision.

A report published by the education select committee in 2013 raised concerns about "consistency, quality, independence and impartiality of careers guidance". A follow-up inquiry last year concluded the situation was not improving.

A review by Ofsted published in September 2013 found only a fifth of schools were effective in ensuring year 9, 10 and 11 pupils were getting the information and advice they needed. Ofsted chief inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw went on to describe careers guidance as a "disaster area" in schools when giving evidence to the education select committee on the role of Ofsted last year.

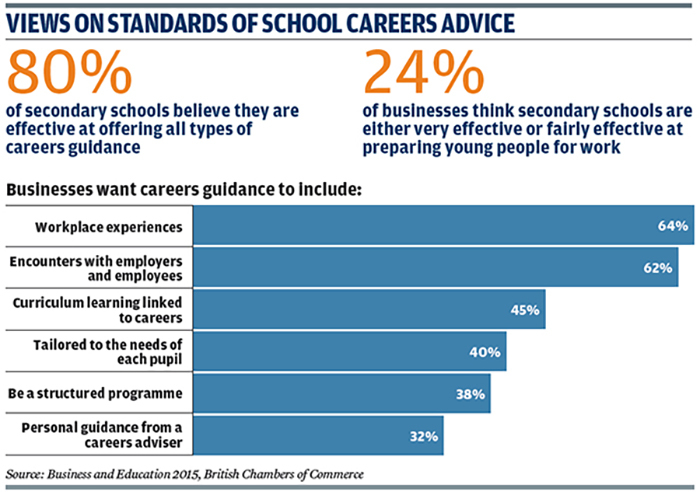

Meanwhile, the business sector has been fiercely critical of the quality of careers guidance. A survey by the British Chambers of Commerce published in November 2015 found just 24 per cent of businesses believed secondary schools were "very" or "fairly" good at preparing children for the world of work (see graphics).

Nevertheless, official figures on the "destinations" of school and college leavers show more young people going into sustained education, training and employment.

The latest available figures, published in January this year, reveal that 92 per cent of young people went into sustained education, training and employment in 2013/14 after Key Stage 4 (GSCE level) up one percentage point on 2012/13 and an increase of three percentage points since 2010/11.

After Key Stage 5 the data shows that 73 per cent of young people go from A-levels into sustained destinations - an increase of two percentage points since 2012/13 and four percentage points since 2010/11.

However, when the figures are broken down by characteristics of pupils it becomes clear disadvantaged pupils are less likely to end up in sustained destinations.

Schools themselves are generally positive about the support they provide. A DfE survey of 107 school and college staff with responsibility for careers provision, undertaken in Spring last year, found 87 per cent agreed or strongly agreed their institution's career guidance programme was high quality as a whole.

Although staff surveyed were generally very positive about the impact and effectiveness of delivery, 31 per cent thought students were not always aware of the provision on offer to them, or of how to access it.

Budget limitations were most commonly reported to be a key challenge in providing excellent careers provision. This has had an impact on the capacity of staff and affected access to professionals with relevant expertise, both internally and externally. Time was also a significant factor - in terms of staff capacity to dedicate to careers provision and for careers teaching within the curriculum.

International research commissioned by the Gatsby Foundation in 2013 saw senior education adviser Sir John Holman, professor of chemistry at the University of York and a former head teacher, identify eight key benchmarks for good careers guidance.

He went on to survey 10 per cent of schools in England and found the vast majority were only fully achieving between none and two of the standards.

Work is now under way to look at how schools can use the benchmarks - now widely accepted and adopted by the careers, education and business sectors - to improve provision (see case study).

Benchmarks improve careers practice

North East Local Enterprise Partnership, careers benchmarks pilot

The North East Local Enterprise Partnership is spearheading a national pilot to test the eight benchmarks for careers education developed on behalf of the Gatsby Foundation by Sir John Holman.

The benchmarks include having a stable careers programme, learning from labour market information, addressing pupils' needs, meeting employers and employees, linking curriculum learning to careers, and ensuring pupils have the chance to gain work experience, have contact with higher and further education, and get personal guidance.

The eight standards are underpinned by a series of characteristics schools must demonstrate in order to achieve each one, explains Ryan Gibson, national facilitator for the benchmarks pilot.

The North East pilot, which started in September last year, has involved 13 schools and three colleges from across the region encompassing a wide range of provision including a pupil referral unit, academies and rural and coastal schools.

Each started by auditing their current provision against the benchmarks. No school or college in the region fully achieved more than three and most achieved between none and two - mirroring the findings of Holman's earlier national survey.

However, Gibson explains many settings were partially achieving benchmarks and the breakdown enabled them to devise clear action plans for some "quick wins" and longer-term pieces of work.

"There was brilliant provision happening everywhere but it wasn't necessarily joined-up within each school and there were some real gaps," says Gibson.

"Some schools had really invested in employer engagement and some had invested in personal guidance but the benchmark everyone struggled with was integrating careers learning into the curriculum so that was an area we have focused on quite a bit."

The benchmarks have what Gibson describes as a "relentless focus on each and every student" and also on "meaningful encounters", whether that is with employers, employees, higher and further education and apprenticeship providers, and guidance professionals.

It is here that greatest progress has been made, he says, especially when it comes to schools investing in independent and impartial careers guidance.

Examples of innovation include the Futures Month run by Kenton School in Central Newcastle, which requires all teachers to teach lessons related to careers and the jobs linked to their subject area. It also features visits from employers, employer-led curriculum projects and work experience.

All schools have been matched up with an enterprise adviser - a senior business person works closely with a senior leader in the school. The Academy at Shotton Hall, County Durham, was matched with the company Caterpillar and they have jointly planned initiatives to prepare young people for the workplace including visits to the firm.

Schools and colleges have made rapid and sustained progress. Every school and college now achieves at least one benchmark and a quarter achieve five "making them comparable to the best we have ever seen", says Gibson.

"Our work suggests there is no magic bullet for good careers guidance - it's about doing a number of things identified in the benchmarks, doing them consistently and doing them for each and every student," says Gibson.